This is the point where someone who wants a feel-good story of how a librarian found their programming grove and learned to be okay with things they wouldn't have been before should stop. It's not the complete story, it doesn't delve into the whys, but it is a good spot to stop if what you're looking for is a motivational-speaker kind of story. From here on out, there's a lot less comedy, because at this point, we start asking why it hasn't always been this way, for kids and grownups alike.

So, one of those things that I have encountered in my travels in academia is the psychologist Carol Dweck's idea of fixed mindsets and growth mindsets. In her 2006 book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, she describes the fixed mindset that's focused on "now" and on the innate abilities and talents of a person as opposed to the growth mindset that believes that what they have now is malleable and changeable (and therefore, can be made better). In the article that inspired the name of this presentation, "Process Over Product: Creativity and Process In The Children's Library", Liza Purdy describes the great frustration that many arts and crafts programs provide to someone who, like me, always has their folds a little off or their drawings a little ish or who can't quite get their work to look like the model, no matter how many times they try.

Product driven arts and crafts[…], especially in projects for young children, not much creativity is used in their execution. […] This definitely appeals to some, particularly those who are able to make their pieces look like the model. But for other kids and adults, it just leads to frustration and bitterness.

I always hated arts and crafts. Handwork didn't come naturally to me, and my arts education was very product based. Everything I made looked scrawny, lopsided and wrong. I would get frustrated and give up, leading to the vicious cycle of continued failure. I wasn’t engaged. I judged myself harshly and felt miserable. As a result, I learned nothing and my abilities were stunted.

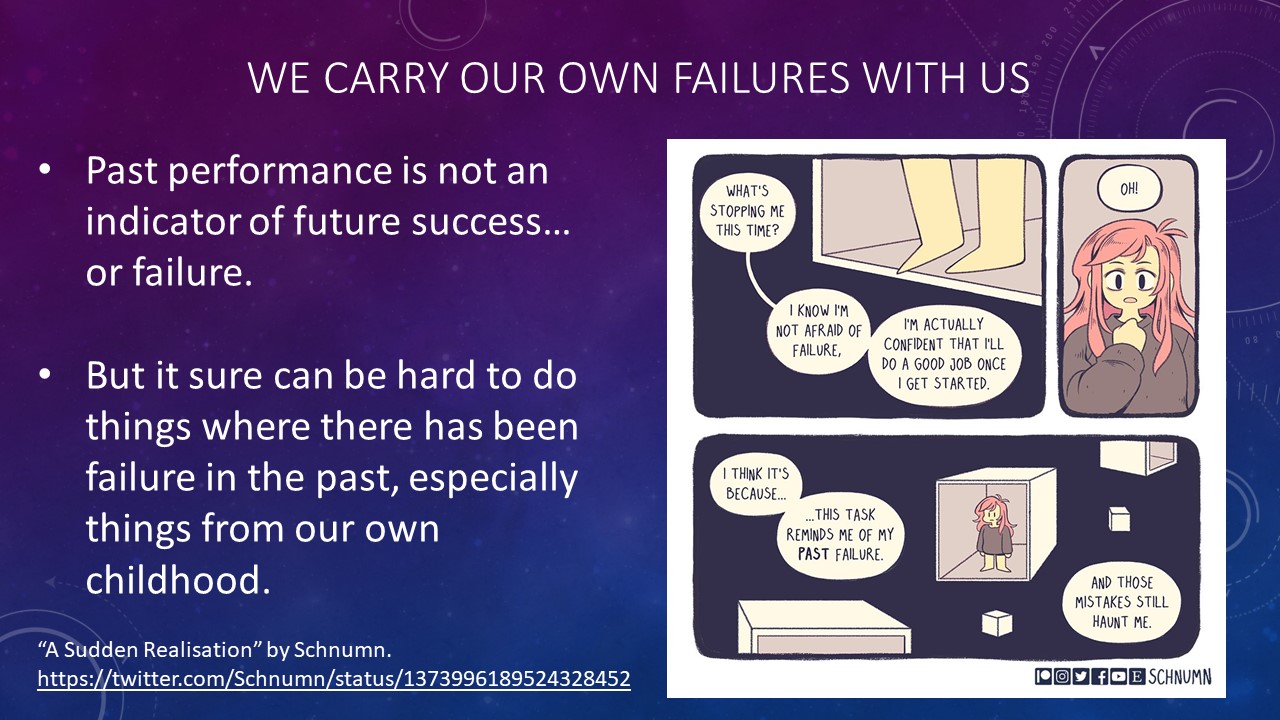

After long enough trying for something that you can't seem to achieve, it seems easier (and healthier for the mental state) to give up on that idea and write it off as something you won't be good at, and to put more time and energy into something you are good at, or that at least produces more obvious signs of skill and success. School encourages this in anything that's not immediately part of the core curriculum, so a person who might turn out to be really creative in a medium or with a technique is put off from it as a child because they don't have support to put in the time needed to develop them more fully at it. (The absolute dearth of arts funding and the restructuring of schools so as to be punitive to the schools that need the most help in achieving test score benchmarks certainly isn't helping.) Thos messages that we tell ourselves (or that others tell us) in our childhood stick with us into adulthood. The things we learned about ourselves as young adults persist into adulthood, and then we get to the ages where we start feeling like you can't teach old dogs new tricks, or that we don't have the time and resources to pick up anything new, at least not until we retire and don't have all of that pressure of work (which is also very much about sticking to a specific thing, rather than being allowed to flex your creativity in approved and safe ways) interfering. The comic from Bex, A Sudden Realization is about someone who, even though they know they've gained the skills to succeed at something, hesitates at actually doing it, not because they're worried they can't, but because the situation resembles something that happened in the past that didn't turn out well at all, and, as noted, "those mistakes still haunt me."

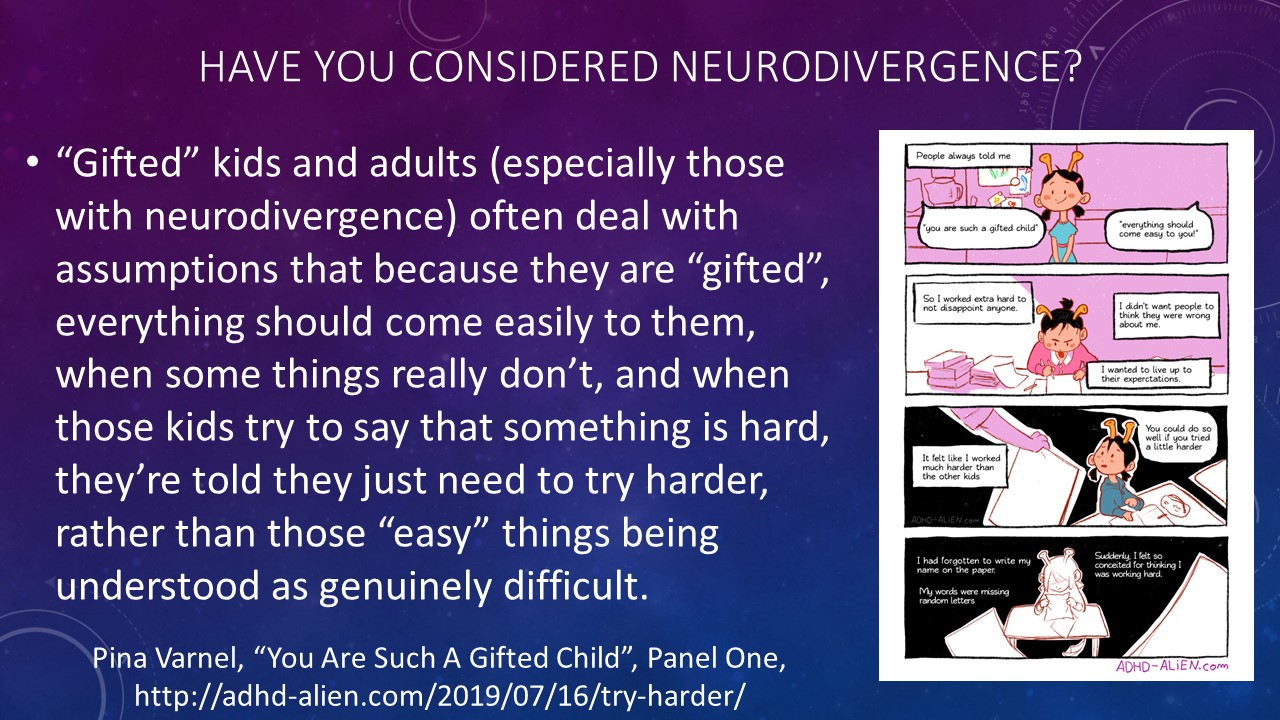

A particularly vicious form of this problem often shows up for kids who are marked as "gifted." "Gifted" kids and adults are often put into a fixed mindset of having an overabundance of talent, but past that, there are different sets of expectations laid on them as to what qualifies as challenging and what qualifies as simple. Some kids have a knack for words, or numbers, or other things, and teachers want to make sure that they're taking coursework that keeps them engaged with that, which can sometimes mean moving up a grade level or more in an attempt to keep things intellectually challenging. (Yes, I passed high school geometry as an elementary school student as well as high school English. No, I don't necessarily recommend it for others.)

The focus on academics can sometimes mean that there's a corresponding lack of focus on social development, and it can also sometimes set up some difficult situations for a "gifted" child, especially one that has a neurodivergence. The kid who has all the facts about things, or who can sometimes focus for hours at a time on something interesting sometimes gets made fun of when it turns out they're pretty average outside of their specific interest, or gets disapproval from their parents and teachers about how the "easy" things, like remembering to put your name on a paper, or, in my case, remembering to put units in, or keeping track of negative signs, turn out not to be so easy at all. Which is correspondingly weird to neurotypical people, because they can't imagine how it looks to someone else, or how such things like those details can get missed. It's un-imagineable to many of them.

Pina Varnel imagines and draws comics about people with ADHD as aliens, with antennae sticking up from their heads, to illustrate the fundamental difference between brains that work in an ADHD way versus brains that work in a neurotypical way, and a lot of the time, the topics are about things like "trying harder" or how someone gets motivated, or the somewhat limited carrying capacity for working memory for someone with ADHD and how that often leads to things like executive dysfunction, time blindness, and other things that neurotypical brains don't have to deal with. (And, extra important for librarians and other mostly-women professions, what might get diagnosed in a boy, because he's disruptive and loud and has to be dealt with, could go sailing by in a girl, because we're socialized to praise a girl that is quiet and reading and otherwise not making a disruption, even if she hasn't heard a word that was said in class the entire lesson.)

René Brooks hosts a website called Black Girl, Lost Keys with advice and suggestions, as well as stories from her own experiences, about what it's like being a Black woman with ADHD. (Because for non-white people, what could be diagnosed tends to be seen as opposition, defiance, or bad behavior, feeding into prejudices about non-white children. This usually means they get suspended earlier and more often, making educational success that much harder by having to do well in an environment that's hostile to learning.) Because one of the common things that comes with neurodivergence is difficulty regulating emotions, a neurodivergent child is often being counseled to be less than the full person they are, so they are acceptable to their neurotypical peers and instructors.

"I can recall often in my childhood when my impulsiveness and enthusiasm were made fun of. I was often told to shut up, told that I talked too much, or that the things I care about were not important.Many ADHD children are raised to believe that they are over the top, too intense, and too much. Not only is it cruel, but it can actually cause ADHD symptoms to worsen. We become accustomed to dimming our lights so we can live among those who are too cowardly to allow their own to shine."

(https://blackgirllostkeys.com/adhd-rejection-sensitive-dysphoria)

Conversely, small setbacks or things that turn out imperfectly can have outsize effects on someone with neurodivergence, with seemingly wild emotional shifts or giant reactions to small things. Or, as in my case, sometimes you get made fun of when you're wrong, because it's novel to the people around you, and they, for whatever reason, seem interested in making sure that the smart person feels stupid when they miss. And that kind of thing, where failure or setback means big emotions and the people around you wondering why you're being such a crybaby or why it's such a big deal for a small thing, or they deliberately set you up to explode because they know you will, leads to something that's different from, but often comes along with, someone's brand of neurodivergence. (It happens in neurotypical kids, too, especially those who are frequently targeted by bullies for being "different" in some other way.)

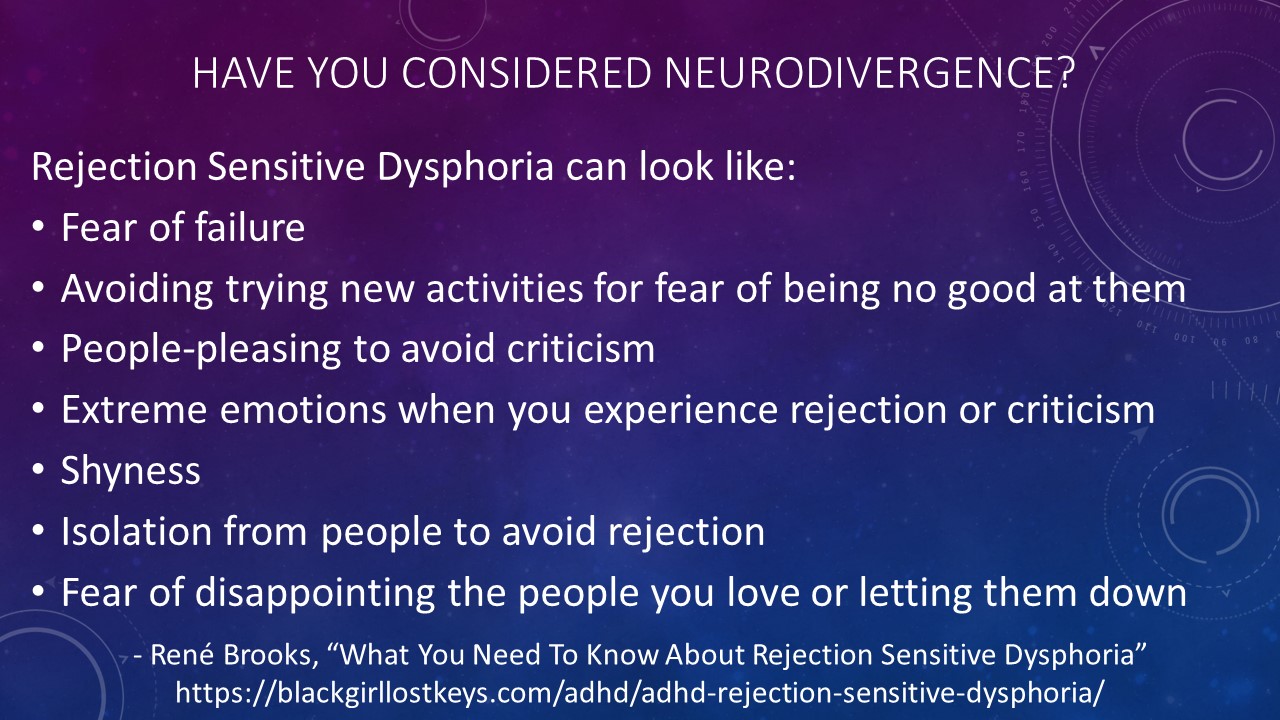

If your experience is such that failure or something other than perfection brings ridicule and disappointment from others, the logical conclusion that comes from that experience, especially when it seems pretty consistent, is never miss. Only perfection can protect you. But, as we all know, nobody is perfect, but for those of us who strive for it because it's the only way to keep ourselves safe, or for people who crash in the opposite direction, of not trying at anything because there's no point in trying when people are only going to criticize you for it, we've probably also got a healthy dose of Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria. René describes some of the outward signs of RSD:

- Fear of Failure

- Avoiding trying new activites for fear of being no good at them

- People-pleasing to avoid criticism

- Extreme emotions when you experience rejection or criticism

- Shyness

- Isolation from people to avoid rejection

- Fear of disappointing the people you love or letting them down

(https://blackgirllostkeys.com/adhd-rejection-sensitive-dysphoria)

…and suddenly it becomes a lot clearer why there might be resistance to product-based programming, especially the kind where there's a model that's supposed to be replicated exactly. Without enough components to allow for "ish" to be good enough, literally, and a design of the program that rewards going through the process, rather than staking it all on the end product, kids (and grownups) who either already have or are developing their rejection sensitivity are going to avoid the thing, even if they really want to do it, because the prospect of being vulnerable to someone else requires so much trust and a lot of kids and grownups have never been shown that much trust or given enough freedom to make something that's theirs and that is seen as equal to ones that might more closely follow the example pattern.

Side note: Remember Deliberate Silly? Remember that kid or grownup in your life who is so much faster off the line to make fun of themselves or to put on an act of some sort when they're around others? Yeah. If you're the one who makes fun of yourself, or tries to make sure that expectations get set really low, then there's no risk of disappointment and rejection of you, the person. It's a question of how well you can play the role, and all the adjustments that have to be made and anticipated so that there's never a reason for anyone else to either find a fault or to get an expectation in their head that you might not be able to fulfill.

Which is to say, this is absolute hell in a work environment. Work environments are almost always strongly oriented toward end products, with no acknowledgment of growth and improvement along the way if there are failures or setbacks, and often in an environment that encourages people to be their most anti-social. Or, people they're being told they have to love and get along with all the time, when that's not possible, either. For neurodivergent kids and adults, if their bosses are incompetent or don't understand what they need to do to help their employee thrive, then it's going to be a bad time. If their co-workers don't understand and feel like the neurodivergent adult is "weird" or somehow not a good "culture fit" because they're different, then the team's not going to produce their best work, and the "different" one is almost always going to be scapegoated for being different. These workplaces are often microcosms of the greater society around, as well, which is saturated with messages about how being yourself is the absolute worst thing you can do if you want to be successful. Even though there are sorts of surface messages about how being yourself is good, most of those messages are advertisements for something to buy to "be yourself" that's still within the strongly-enforced boundaries of what "normal" is.

I speak from experience here, because even though, at the time of this presentation, I'm now "mid-career," I almost got fired from my current position as an early-career librarian. My first boss, now retired from the system, believed firmly in the value of swift and escalating punishment for mistakes. I learned this early on when I accidentally messed up a library card application by forgetting the exception to the rule about who couldn't get a library card. I put together a flowchart for my own understanding and to demonstrate that I had learned from my mistake and wouldn't be doing it again. It appeared on my evaluation one year that at least one of the school librarians I had been assigned to complained that I lacked "classroom management skills," despite never having been trained on how to handle a classroom of students that I was trying to get hyped for the Summer Reading program. I pointed out that the librarian who made the complaint was trying to do last-minute inventory, and that the teachers had left for their planning periods, so I didn't have any support from any of the people the students knew could make things difficult for them if they misbehaved. My job was to get them hyped and ready for Summer Reading. Apparently, it also meant that I had to be able to exercise control and discipline over them using skills that I never knew I needed.

During that time, I also had at least one co-worker who was actively trying to get me in trouble, at least according to one co-worker who also routinely seems to be trying to get me in trouble, over different things, apparently. It all came to a head where, in trying not to fall asleep during a meeting of the Friends of the Library late at night, (the reasons why I was having trouble staying awake, I wouldn't discover for a few more years yet) I stood and took a standing position nearby where I could still listen, but not doze. This was apparently perceived and reported as being rude to everyone, and so that was the thing that got me put on disciplinary probation, in addition to all sorts of other things that were always met with "Stop being weird. You should just know not to do these things." Or just know to do these other things. Or to not do things that are potentially within my job description, but that the manager or coworkers don't understand as within my job description, because those will be seen as suspicious and not-work. There were expectations that nobody bothered to explain to me, there were systems of power being used that I still don't fully understand, and so, when confronted with "Well, how are you going to fix these things?" the best I had was "Well, you'll have to trust me, I guess?" because the problem space still hadn't been explained to me in any way that made sense so that I could try to fix it, and no concrete suggestions or systems had been propsed to me that would be a way of showing that I was doing the things that were asked of me.

So I spent six months of my career completely terrified that one day, I was going to be at work, and I was going to get called into an office and told "You're fired." (That's what being on probation again meant - I could have been fired for any reason at all. As best as I could tell, that included something like "I don't like your shirt," even if it would have been written up as something like "disrespect for a manager" or something like that.) How is anyone supposed to function in an environment where your continued employment rests solely on whether or not you've aggravated someone who has the power to fire you, or who has the ear of people who have the power to fire you and decide to use that connection maliciously?

I still get feedback from my current supervisor about things that other people are complaining to him about me. This is confusing to me that they don't, say, talk to me about what they would like, and instead leave vague messages with my supervisor, which makes it really hard to do the thing that they would like me to do, because I don't do all that great with "be more proactive about this," where "this" is a category that includes many different specific things that could be done that would alleviate the problem. Even though my current supervisor tries to impress upon me the relative problem levels of the thing when giving the feedback, so I'm supposed to have an idea of how serious the thing is, I've spent a lot of my life where things that should be no biggie turn out to secretly have been very big deals and I was supposed to intuit that. So instead, for safety, I try to treat everything as a bigger deal than it might be, because small things becoming big things was what happened the last time someone tried to get me fired.

Sometimes, even if we want to focus more on process, on growth, on learning and change, and on trying to put on programming that reflects these values, we find that outside forces intend to never let us do such things. If our administrators and supervisors punish us for trying to be creative and take risks, if our co-workers sabotage our efforts, if the work environment we are in or the community that surrounds us is hostile to the idea of doing things differently, creatively, taking a risk, or otherwise trying to expand our horizons past "this is always the way we've done it, stop trying to rock the boat," especially those that might not end up with a concrete product to wave around in front of the people who fund and manage the library, then most of our efforts will be dead before they have the opportunity to thrive.

That's a lot of heavy content. It might have stirred up some feelings in you, or it might resonate with you a lot more than you wanted it to. I wanted to take a moment here at the end to acknowledge that, because the people that you would really like to acknowledge this often don't. Some parts of this may ring truer for you or for the people who come to your organizations and your programs. Like a lot of presentations, this isn't supposed to be the final and authoritative word on the matter, even if I do want to encourage you to switch more toward using programs that reward the process over the product. I can really only talk about the things that helped me and the things that would have helped me in the past. So, in the most sincere way, I hope this helped you with something. (And if it did, it'd be really neat if you let me know. There's precious little of talking about the good things in libraries.)